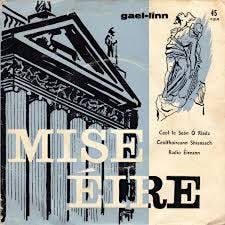

Kino Gaelach: 5 scannáin every Gael must watch

Cinema does not have to be an instrument of Anglicisation, but a means for our liberation.

The necessity of Gaelicising Irish cinema

The success of the Kneecap film this year demonstrates the potential and momentum of scannánaíocht as Gaeilge, along with the recent successes of An Cailín Ciúin and others in previous years. A long-awaited golden age of Irish-language cinema may await us, but it’s worthwhile appreciating the classic works of Gae…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Aistí ó Chraobh to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.