Let the Dissidents Sing: Rebel Anthems which need to be reclaimed

Our traditional folk music is rife with themes and tales which profoundly contradict the ethos of Neoliberal Ireland.

The Rebel Songs debate

As days go by the headlines continue to mount around whether rebel songs like The Wolfe Tones’ Celtic Symphony are acceptable for the country’s cultureless Neoliberal establishment. The ‘Good People’ of D4, as Fennell referred to them, have always been disgusted at songs glorifying the nation’s historical struggle for independence. Their preference has always been aligned with meaningless platitudes like Ireland’s Call, devoid of history or ideals — or worse, to pretend we never had a revolutionary period at all, with all the sacrifice and idealism it inspired, hence the recent murmuring about getting rid of the (actual) national anthem altogether.

While the debate is interesting, an opportunity is lost if cultural dissidents merely opportunistically affirm jingoistic RA-songs in an attempt to position themselves as edgy and anti-cancel culture. Celtic Symphony is a roaring tune, and obnoxiously chanting it at clubs to own liberals is funny — but, there are far more genuinely illiberal and counter-cultural anthems in the Irish rebel tradition, which can honestly be claimed by dissidents in modern Ireland.

Fenian Anthems (O’Donnell Abú & God Save Ireland)

For instance, the Fenian ballads of the 19th Century, which are still regularly heard at trad pubs around the country, are rife with themes that Ireland’s technocracy detest.

One such example is that of O’Donnell Abú, written in 1843 at the emergence of Young Ireland’s cultural romanticism. Celebrating Red Hugh O’Donnell, the Gaelic leader of Tír Chonaill against the Brits, the song is an unadulterated ‘war-cry’ set to a marching bodhrán rhythm. With some poetical references to rivers like Lough Swilly and the Bann, the lyrics straightforwardly portray O’Donnell’s Gaels as ‘war-wolves’ on the hunt for British ‘strangers to flight or fear’. Has there ever been a more explicit expression of the ancient notion of ‘tírghrá’ in the English language?:

‘Make the false Saxon feel, Erin's avenging steel!

Strike for your country! "O'Donnell Abú!"‘

Through its simplicity, the tune cuts through cynicism and irony and embraces a fundamentally sincerist jingoism. Sharing the energy of soccer hooligan machismo, the continued popularity of it and similar tunes in trad circles opens an avenue for dissidents to celebrate a masculinist Gaelicism.

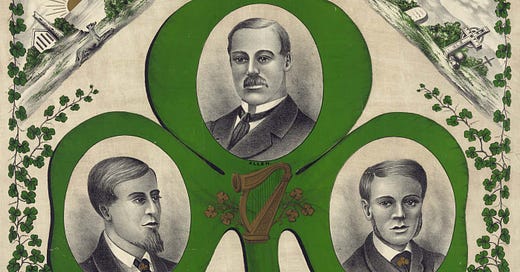

Also of the Fenian-era is God Save Ireland, the unofficial national anthem before Amhrán na bhFiann. Its subject matter emanates from the execution of the Manchester Martyrs, three Irishmen accused of plotting against the British police. As the name suggests, the song has a more explicitly Catholic theme than O’Donnell Abú, depicting the Irish struggle as a righteous ethno-religious cause:

‘By the vengeful tyrant stricken in their bloom; But they met him face to face, with the courage of their race,

And they went with souls undaunted to their doom.’

The battle is for ‘holy Ireland’, indicating that the fight for freedom is not one of political materialism, but of a spiritual metaphysic — to save Ireland is to save the Soul of our race. The fact that the jingle was sung by the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the heroes of 16 while they occupied the GPO, simply adds more emotional resonance to the thumping chorus. A chorus which militant secularists simply cannot appreciate the same way dissident Catholics and critics of Nihilism can.

Sean Nós of the Wandering Gaels (Trasna na dTonnta & An Poc Ar Buile)

Greatly expanding the themeatic variance of Sean-nós, but perhaps lacking the anthemic vigour of these songs, the post-Famine period saw a rise in slower balladry about the masses of emigrants leaving the country, yearning for a literal — as well as metaphysical — return to Éire.

Many of these songs bnurseryear the style of nursery or children’s rhymes, presumably taught to the second generation emigrants from the country, in attempt to preserve the spiritual ethnos of the previous generations. One such example is Trasna na dTonnta, a well-known gaelscoil sing-along nowadays. A wistful tune for a wandering people, the story evokes an overwhelming feeling in the listener to return to one’s roots and ancestors, a return to their ideals and values — a return to Ireland. The pertinence of the second verse for modern Ireland can’t be overlooked:

‘Chonaic mo dhóthain de Thíortha i gcéin, Ór agus airgead, saibhreas an tsaoil,

Éiríonn an croí ‘nam le breacadh gach lae, ‘S mé druidim le dúthaigh mo mhuintir!’

(I saw my fill of countries abroad, Gold and silver, the wealth of the world,

My heart rises in me with the break of each day, As I draw closer to the land of my people!)

With the modern Irish state overseeing and maintaining a rapid outflow of our nation to every faraway part of the globe, particularly our young, the notion of looking past all the glamour of the world for one’s roots is incredibly powerful, if largely unfeasible for many.

Once again, one wonders how cosmopolitan neoliberals, totally embracing of Americanised Ireland’s culture of liberal-consumerism and spiritual nihilism, can appreciate the theme of staying loyal to one’s people and soil.

Similarly, An Poc Ar Buile, a song which remains enormously popular in Gaeilgeoir circles, is a raucous romp for the Gaels need to reclaim their lands. Perhaps one can understand the tolerance of this song above others, as the theme of revanchism is told metaphorically through the revolt of a mad Goat at the Killorglin Puck Fair, and its underlying meaning is often overlooked. The reduction of the song to the ‘quirky irish’ stereotype must be resisted — though it is humorous. Instead, the chaotic goat is a warning sign of Cromwell’s invasion, and a power of chaos for all rebels against the state:

‘Bhí garda mór i mBaile an Róistigh, Is bhailigh fórsa chun sinn a chlipeadh,

Do bhuail sé rop dá adhairc sa tóin ann, S'dá bhríste nua do dhein sé giobail.’

(When the sergeant stood in Rochestown, With a force of guards to apprehend us,

The goat he tore his trousers down, And made rags of his breeches and new suspenders.)

In a sense, the mad Goat is a perfect representative of the Rebel tendency within Gaelic culture writ large. The chaotic image of maverick Gaelic Autism, clashing against the stiff-upper lip Angloid, is a consistent theme in traditional Irish culture. As Gaeilge, the term would be Tóraíocht, which of course has particular political relevance as the origin of the term Tory, for the British Conservative Party (who were originally slandered as sympathetic to Catholic Irish Rebels). While archaic, this again demonstrates the Rightist origin of much of Gaelic culture.

Independence and Beyond (Seán Tracy, Sean & South of Garryowen)

Following the lamenting balladry of the post-Famine period, the Independence Era of the 20th Century saw a full revival of assertive rebel songs. Perhaps more than any other era, much of these tracks are directly tied to a totally illiberal politic of Gaelic ethno-particularism.

One such example is the popular ballad, Seán Treacy, named after the famous leader of the Tipperary Brigade during the Irish War of Independence. In the spirit of slower laments like Boolavogue, Treacy’s infamous sacrifice on Talbot Street is immortalized like the Aisling of Gaeldom. His death here mirrors the fall of so many great Fenians, Sarsfield among others, who died thinking of their native land: ‘"No longer on earth can I stay, I will never more roam to my own native home, Tipperary, so far away"’. His personal brand of Irish Nationalism reinforces the theme of preserving one’s local identity, with Treacy famously writing from Dundalk jail in 1918:

‘Deport all in favour of the enemy out of the country. Deal sternly with those who try to resist. Maintain the strictest discipline, there must be no running to kiss mothers goodbye.’

Of course, one can detest this type of cultural militarism while appreciating the ballad. The point being that dissidents who propose a dogmatic revival of Gaelic Independence, in the face of looming Neoliberal tyranny, lose a great opportunity by not claiming Seán Treacy and his accompanying famous ballad.

Even more so, one of the most famous and beloved 20th Century rebel songs of all, Sean South of Garryowen, about the failed 1957 IRA raid on RUC barracks in Fermanagh, is a given necessity for dissidents to know. With little to no chorus or repetitive refrain, other than the references to Limerick, its continued success is a testament to the song’s rousing pace, chugging along from the opening spoken verse describing the sad ‘homes round Garryowen’ to the the bellowing cry to remember the sacrifice of South and his men:

‘They have gone to join that gallant band, Of Plunkett, Pearse and Tone

A martyr for old Ireland, Sean South from Garryowen.’

That ‘old Ireland’ referred to is illuminated by a study of South’s personal politics. Even in De Valera’s famously reactionary Ireland, he was known as a militant Catholic, founding the local Limerick branch of Maria Duce (a radical right organisation) and affiliating with Conradh na Gaeilge groups like Glún na Buaidhe, which also had rightist sympathies. South’s anonymous essays in the Limerick Leader leave little to the imagination, strongly denouncing perceived Masonic infiltration into Ireland through American mass-media.

From his own period, to today, South was a national dissident. While it would be LARPy and unnecessary to artificially align oneself with South’s views because of appreciation of the song, the obvious cultural power of claiming the man and his ballad goes without saying. That ‘gallant band’ lead by South were fighting for something more than a united liberal republic, they dreamt of a truly independent Nation, Gaelic and Free — and it is the responsibility of every dissident to remember that fact.

Rebel songs for the future?

If dissidents are to appeal to people, they naturally have to offer more than statistical truisms and rationalistic arguments. Masses of normal working people are won by the heart first and foremost, with reason following afterwards. And so, the question arises, what will the future of the rebel song look like? Who will continue to sing of O’Donnell, An Poc Ar Buile and Sean South? — long after the country is ‘unified’ under the rule of secular globalised Capital?

Who are the heirs of our rebel tradition in modern Ireland?

Love this! I wrote a piece about An Puc At Buile myself and the aftermath of Storm Eowghn