Desmond Fennell's analysis of Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project and the West's Decline

Desmond Fennell's infamous work 'Uncertain Dawn' attempts to link the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the beginning of the end of the West.

‘Bergen thought of the Israelis sitting there in their desert oasis, their atom bombs wrapped in the Talmud. An excitable people, he thought.’ - Frank Herbert, The White Plague.1

OPPENHEIMER: ‘Lawrence, you embraced the revolution in physics. Can’t you see it everywhere else? Picasso, Stravinsky, Freud, Marx...’

LAWRENCE: ‘Well, this is America, Oppie. We had our revolution.’2

Fennell and Oppenheimer

Cillian Murphy’s recent victory at the Oscars for his performance in Oppenheimer has already done a lot to solidify Ireland’s boom on the global stage in American blockbuster culture. What is interesting is, in all of the praise of Murphy and his portrayal of the titular physicist responsible for leading the Manhattan Project (and the subsequent dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki), there has been no controversy or debate about the historical apologetics of the film.66

Nolan, who has not been shy about producing potentially culturally offensive films —such as The Dark Knight Rises’ parody of Occupy Wall Street — has managed to make a film largely defending those responsible for Hiroshima and Nagasaki without any of a controversy whatsoever. While there are scattered lines about Oppenheimer feeling ‘blood on my hands’, they are mostly concerned with the future ramifications of nuclear war and the H-Bomb, as opposed to the any legitimate regret about Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In fact, the genocide of those two cities is largely removed from the film, with very little reference or serious discussion of the crime which took place. What this suggests is, neither official Ireland or the Western woke media truly find anything significantly objectionable about these massacres, which for our sanitised liberal climate, is somewhat bizarre.

Thankfully, Ireland’s greatest 20th Century philosopher, Desmond Fennell, pondered this exact subject deeply, in his 1996 work Uncertain Dawn: Hiroshima and the beginning of post-western civilisation. For Fennell, he found the massacres of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be a fundamental breaking point from the Christian heritage of the West, into a new order of post-Hiroshima civilisation. He points to the Protestant Federal Council of Churches, the various Catholic papers at the time like Commonweal and others to solidify what Fulton Sheen argued the proper Christian position on these massacres is, that namely: ‘Once the primary consideration is the winning of a war without regard to the justice of war, then all men are reduced to vermin’.3

Throughout the work, Fennell tries to understand how and why this break from traditional Christian ethics, which would have opposed the mass industrial slaughter of civilians, could have occurred. He begins by detailing the obscurity of modern American life, particularly which he witnessed in his stay in Seattle, seeing it as a civilisation which appears to be based on a false premise of cultural life, perhaps indicative of a fundamental error which had occurred in its recent history. In particular, Fennell is horrified by the anti-human erasure seen in a culture of progressivism, abortion and euthanasia — a worrying comparison with some modern Irish trends.

Fennell’s analysis of post-Hiroshima 20th Century America

Fennell was particularly struck by the peculiarity of post-Hiroshima American civilisation in the erasure of Western personhood in the new ‘HR’-enforced order of identity categorisation. As an example of this, he details how his advertisement seeking an apartment to rent in Seattle was rejected by a newspaper due to legal advice which said no tenants can refer to characteristics such as ‘male’, ‘Christian’ and / or ‘Irish’. Upon further inspection, Fennell found that various American ‘Fair Housing Acts’ prohibit listing a whole range of normalised identity labels, such as your Sex, Religion, etc – even ‘“Adult”, “one person”, “couple” banned”’.4

For Fennell, this amounted to a ‘mindless, random trampling on personal freedom as the new prohibitions, by golly, replace the old, and all considered OK because it’s in a noble virtuous cause’.5 Owing to the shift in civilisation to a non-normalised culture, he argues that it is reflective of a multiculturalist ‘cult of difference’:

‘Another overriding absolutism is at work here. Not nature this time, but “difference”, is the cult object. Not discriminating against those who are “different” from you means “respecting difference”. It ties in with what they call “multiculturalism”.’6

Naturally, this attempt to enforce a homogenized and uniform identity which is sexless, raceless and so on, has simply backfired with the heterogenous cultural nature of mass-urban civilisation. Attempts to impose ‘indifference’ where there is identifiably ‘difference’ have simply lead to more distinction and tension becoming apparent in everyday life:

‘The ideological emphasis on “respecting difference” in physical/racial types…and the arming of the “different” types with legal “rights” and “entitlements”, has strange effects. I have an impression of all these types going around like pocket battleships, armed with guns on all sides—the guns of their legal rights as “protected species”.’7

This tension is largely inevitable when you have weaponised groups, armed against that ‘the norm’, while the majority of citizens are excluded from even recognising difference and distinction. The same ambiguity, according to Fennell, is played out in gender relations. Young women in the 90s were told by Andrea Dworkin, somewhat accurately in my view, to strongly oppose sexual promiscuity in men (to the point of being recluse femcels) — while Gloria Steinem and others advocated for the celebration of prostitution.

For Fennell, this created a strange effect, the ‘angel-whore dichotomy’ — where young women could either become totally sexless or embrace promiscuity. Anti-sex Feminism enforced a business puritanism among men and women, creating ‘a chaste atmosphere, the absence of sexual interaction’ and insured that the ‘appraising sexual glances of the old civilisation had died’ — all the while the prostitution of objectified young women was openly advertised in newspapers.8

This leads to a total discordance, where sexual relationships are removed from the intimacy of committed monogamy and relocated in the exploitative producer-consoomer relationship of prostitution:

‘[There was no] continuum, between the female face the town was showing me and this….I had a vision of Seattle males and females rushing home to their phones to dial a number and say “Whew, that was awful. Thank God I can be natural now!”…the great campaign for women’s rights, has reproduced the Victorian dichotomy of “women as angel and as whore”.’9

Interestingly, Fennell goes on to recognise that this state of affairs between men and women ‘seems to be what the regime and the state class want’ based on the way in which the campaign of Feminism ‘was transmitted, magnified and driven home by the media, and supported by the legislators and the courts’.10

The question which arises from this, in my view, is cui bono? — to whose benefit is this isolation and atomisation of gender, racial and cultural life in modern America?

The ‘Differentist’ revolution against Christendom

Thankfully, Fennell himself hints toward an answer to this question, pointing to what he calls ‘Differentism’ which is a sort of ‘grant enterprise of multiculturalism’ carried out by a loose coalition of groups which seeks to dislodge the norm of Western, Christian patriarchy. He dismisses the notion that the real powers behind this push relate to ‘women, cripples’ and other minorities, but instead are made up of ‘Normal white men’ who (I quote at length to illustrate the point):

‘in particular still run the East Coast, where political power (financial, legislative and media), and elite academic influence, are concentrated. Logically, then, it was a major section of this Eastern male establishment, helped by their class and kind throughout the nation, which gave the green light to the difference cult, made it powerful in the media, and had it enforced by law….

…These men gave ear to the activist groups that attacked normal white men on behalf of “minorities” and women. Conceding the activists' complaints and fomenting them, seeing to it that their message was heard and extensively funding their existence, they not only permitted, they propagated and enforced differentism.’11

This is a crucial aspect in understanding Fennell’s emphasis on what he calls the ‘Godless, post-Hiroshima’ project of American civilisation in the later 20th Century. While he acknowledges the traditional WASPs from the heartland went along with this project because of guilt, there is a clear contention that the anti-Christian / anti-Western character and ideology of those who developed the atomic bomb with those ‘Eastern’ elites may have lead the cultural war on Western civilisation after the war. In this sense, the Manhattan Project could be seen as the culmination of a new, non-Christian and anti-Western element taking the driver’s seat in the American empire.

For Fennell, the religious aspect to this managerial transformation is absolutely essential. He highlights that the project for building the Atomic bomb was named ‘Trinity’ by Oppenheimer, who was deeply invested in cabbalistic mysticism and esoterica:

‘not only Oppenheimer, but the community of scientists at Los Alamos, were planning to detonate their bomb at a place which their leader had deliberately named after the Christian God. In the light of this alone, the Manhattan Project—as the scientific enterprise was called—acquires a religious dimension. It was, in effect, for the scientist-priests involved in it, an investigation of nature’s powers with the purpose of hurling it in the face of the Christian God.’12

This ‘investigation’ of powers outside the desire of the Christian God and metaphysical ethic may have been inspired by our modern reintroduction or cabbalistic reinterpretation of the ‘vengeful Yahweh’ of the Old Testament:

‘A matter upon which we can only speculate is the role of the God of the Old Testament in the minds of the Bomb’s makers and political sponsors. Unlike the God of the New Testament—the Christian God—Jahweh was a massacrer. His Jewish devotees believed that He massacred on their behalf, celebrated Him for doing so, and invoked Him to so.…

…Given this shared religious background, Jews and Protestants of Old Testament persuasion, who were involved with the Bomb must have seen a parallel between the use to which nature was being put against Japan, and the role of Jahweh as massacrer and avenger of his people.’’13

Fennell concludes this mental exercise reminding the reader of the revolutionary potential in the bomb as a rejection of Christian ethics and metaphysics, as, for those in whose eyes the ‘Christian God was lamentable aberration from the true God, the Bomb could signify a religiously justified rejection of the usurper, and the reassertion, in updated terms, of the ways of Jahweh.’14

The Manhattan Project’s ideological currents

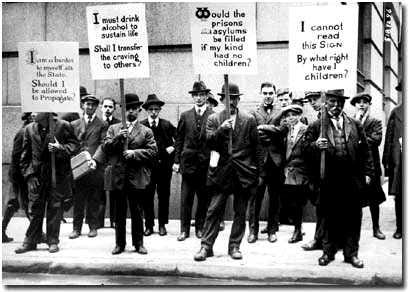

While few of the physicists involved in the Manhattan Project were openly religious, it has been noted, or celebrated depending on the author, the proportion of non-Christian religious minorities who dominated the names of the physicists. Medzini notes that ‘of the heads of sections in charge of the Manhattan Project, at least eight’ were of a minority ethnic background. Which, for the WASP United States at the time, is historically significant.

He lists the most significant names as ‘Edward Teller, Eugene Wigner, Leo Szilard, [who were] all Hungarian’. Then there were the Austrians ‘from Vienna came Victor Weisskopf. Max Born, James Franck, Hans Bethe and Otto Frisch were born in Germany’, and finally there 'were native-born Americans – Isadore Rabi, Richard Feynman and Eugene Rabinowitz.’15 It’s worth asking the question, did these cultural roots impact any of the relationships with the traditional WASP establishment in any identifiable way?

Of those scientists in the Manhattan Project who did feel a sense of cosmic guilt and and moral opposition to the ‘new order’ of Hiroshima, there is a striking absence of these various aforementioned minority names. Some of those who spoke openly about their opposition were: Philip Morrison,

Certainly, this contrast between the Western, Christian order of America and the new revolutionary one can be seen in some of the personal relationships between the scientists and strongmen. For instance, American engineer Leslie Groves, the somewhat disconnected director of the Project often clashed with the physicist personalities, especially that of Hungarian physicist, Leo Szilard. According to the biographer of Szilard, Groves’ archetype was that of the ‘perfect villain’, personifying the authoritarian, Western male:

‘Groves was an all-American boy, active in sports and devoutly Christian, a patriotic militarist and engineer, while Szilard was an Eastern European immigrant, active in science and spurned both the military and engineering. Grove’s authoritarian rectitude and anti-intellectual swagger clashed with Szilard’s austere reason and playful erudition’.16’

I’s worth briefly considering what kind of intellectual influences the physicists encouraging nuclear armament may have had. Oppenheimer is particularly famous for his quotation and meditation on the Bhagavad Gita’s ‘I have become Death’ phrase, however many accounts fail to make note of the influence of Felix Adler’s Ethical Culture Movement. Oppenheimer attended an ‘Ethical Culture’ school all through his childhood. As a precursor to the nihilism of the 60s, the Ethical Culture movement passionately advocated for the right to euthanasia as a form of radical liberation. One wonders if a young Oppenheimer may have been swayed by this sort of philosophical death-cult.

Certainly Fennell found that a Seattle court case justifying the ‘right to die’ exemplified all that was corrupted and non-Christian about this new American civilisation he found himself in:

‘I am as conscious as are the Americans who are objecting, that this is a momentous break with the inherited morality about killing, and a move into uncharted country. I realise it is a break not only with the Christian ethical tradition common to Europeans and Americans but also with its Graeco-Roman underlays, and therefore with the entire ethical system which has characterised the West since Emperor Constantine made Christianity the religion of the Roman empire.’17

A far more extreme example of this death-worship was that of the ‘Suicide Squad’, a group of rogue rocket engineers and scientists who emanated from very similar circles in Caltech as Oppenheimer. Most famously, there is Jack Parsons, who is commonly considered the ‘God-father of NASA’, who was a communist associate of Frank Oppenheimer, Robert’s brother. Parsons practiced sex-magic, radical liberalism and saw himself as embodying, quite cartoonishly, the ‘Oath of the AntiChrist’.18 Among his circle of Liberal sexual occultists, the dropping of the Atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki were considered subversive triumphs:

‘In Parsons circle…[Aleister] Crowley wrote excitedly to one of his disciples, explaining that The Book of the Law had foretold the bomb in its verses, “I will give you a war-engine / With it ye shall smite the peoples; and none shall stand before you.” The science fiction fans were stunned by, and almost perversely proud of, the prescience of their beloved stories’19

While we may never know the exact motivations or justifications for the scientist-priest class agreeing to develop the weapons of mass destruction, what becomes clear is that they were not motivated by traditional Christian ethics and metaphysics.

Debate in the Nuclear West

Certainly, the notion that there was a non-Christian element behind those who led the Manhattan Project and the persecution of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been expressed by some Japanese dissidents. As Miyazawa and Goodman report, the concerns that certain American secular forces have hurt and continue to ‘threaten Japan’s national security persisted and was promoted by extremists on both the left and the right’ throughout the 20th Century.

This view was held by Yajima Kinji, an internationally renowned economist, among others. However, for the purposes of this discussion it is important to make reference to the extremist anti-Imperialist group, “The Committee for Palestinian Studies”, who emphasised the peculiar connection with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In their totally conspiratorial pamphlet (which the author of this work most certainly rejects), Merchants of Diamonds and Death, the author insists South Africa and Taiwan as a sort of absurd nexus of evil:

‘These three countries have entered into a tacit alliance of murder. Devoting their energies to the most illicit of industries, they are in fact shaping world events…the fact is that early on they secretly cooperated in developing the atomic bomb. Not only have they given birth to the most dangerous alliance in terms of global strategy, but they have been directly involved in every conflict and war and are sending an endless stream of arms, munitions, and military advice into the fields of battle.’20

Frank Aiken truly solidified his status as a hero of Irish diplomacy with his tireless advocacy against nuclear weapons. After having his Non-Proliferation advocacy rejected in 1958 Aiken eventually has his proposal adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1961 -- the first resolution broaching the topic. In 1968 he was the first signature of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in Moscow. Kelly summarises his work well:

‘It was this steadfast commitment to nuclear disarmament, and his role in successfully securing an agreement at the UN between the Americans and Soviets on this issue, which remains Aiken's abiding legacy and greatest achievement as Minister for External Affairs.’21

While it may seem only partially relevant, it is worth noting the role (albeit small) Ireland has played as a bulwark against the new post-Hiroshima civilisation American civilisation. As we a small country, we may always be on the periphery of the broad geopolitical and civilisational shifts of the major players — but that does not mean Ireland cannot still be a leader of a spiritual empire once again. As the Western world moves toward a uniformity of managerial technocracy, with sanitised speech, a culture of death and an abandonment of our Christian heritage — Ireland could resist the post-Hiroshima demands of homogeneity, in favor of a radically independent Christian moral order.

Bibliography:

Alperovitz, Gar. 1995. The decision to use the atomic bomb.

Evans & Kelly. 2014. Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist.

Fennell, Desmond. 1996. Uncertain Dawn: Hirsoshima and the beginning of post-western civilisation.

Garrison, Jim. 1982. Theology After Hiroshima.

Herbert, Frank. 1982. The White Plague.

McSweeney, Bill (eds). 1985. Ireland and the threat of Nuclear War.

Medzini, Meron. 2009. The Making Of The Atomic Bomb.

Miyazawa & Goodman. 1995. The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype.

Pendle, George. 2005. Strange Angel.

Herbert, p.140.

Nolan, Christopher. ‘Oppenheimer’, about 20 minutes in.

Fennell, p.4.

Fennell, p.97.

Ibid.

Ibid, p.98.

Ibid, p.112.

Ibid, p.106.

Ibid, p.107/

Ibid, p,108.

Ibid, p.118.

Ibid, p.36.

Ibid.

Ibid, p.37.

Medzini, p.127

Ibid, p.139.

Fennell, p.22.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Parsons#Loss_of_FBI_clearance,_Red_Scare_Marxist_and_espionage_accusations_and_acquittal:_1946%E2%80%931952

Pendle, p.172.

Quoted by Miyazawa and Goodman, p.218.

Kelly, p.46.