Haugheyite Populism: The ideology behind Irish electoral success (Fennellism, pt. 1)

As Charlie's Populist rhetoric and bombast dominated Irish elections in the 80s, through his Sunday Post column, Desmond Fennell laid out the intellectual case for Irish Populism.

The redneck’s Haugheyite revolt*1

‘A minority of nice, reasonable, descent, sensitive, enlightened people are engaged in a struggle on many fronts against a majority of boorish malevolent rednecks.’2

‘Anois tá a cuallacht á caoineadh, gheibbeadh airgead buí agus bán;

's í ná tógladh sillbh na ndaoine, ach cara na bhfíorbhochtán.’ — Caoine Cill Cháis.

‘From southern glens to Aston Shores, The ancient cry of freedom roars

From Northern hills to Leinster’s doors. We’ll rise and follow Charlie!’ — Arise and Follow.

With this month’s local and EU elections there has been one theme dominating coverage: that of ‘the spectre of populism’ haunting Irish democracy. For years Ballsbridge, Irish rugby fans and our data-driven Derek-class have lived in a period of Arcadian bliss with Ireland’s lack of populist resistance. Our neoliberal technocracy has been uniquely secure, manoeuvring through recessions, the water charges crisis and a soft cultural coup without a murmur of real alternative electoral results. Except now.

And so, I’ve decided to look back on the last time the Irish electorate swung toward (at least rhetorical) populism, in the successes of Charles J. Haughey’s formulation of Fianna Fáil through the 1980s.

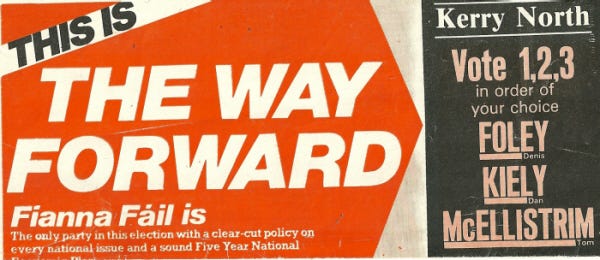

I am not interested in relitigating the history of 1980s Irish elections, but the general picture is worth covering. From February 1982 to June 1989 Haughey led Fianna Fáil to victories in 3 out of 4 contested elections — as well leading the way to landslide wins in two hotly contested referendums on abortion and divorce.

Perhaps even more defining than his mere electoral successes was the way in which he won, utilising a radical, syncretic amalgamation of populist constituencies. Contrary to the stately old guard of the party, Haughey’s political force was youthful, bombastic and relied on mass-populist energy — both from small towns as well as neglected city centres.

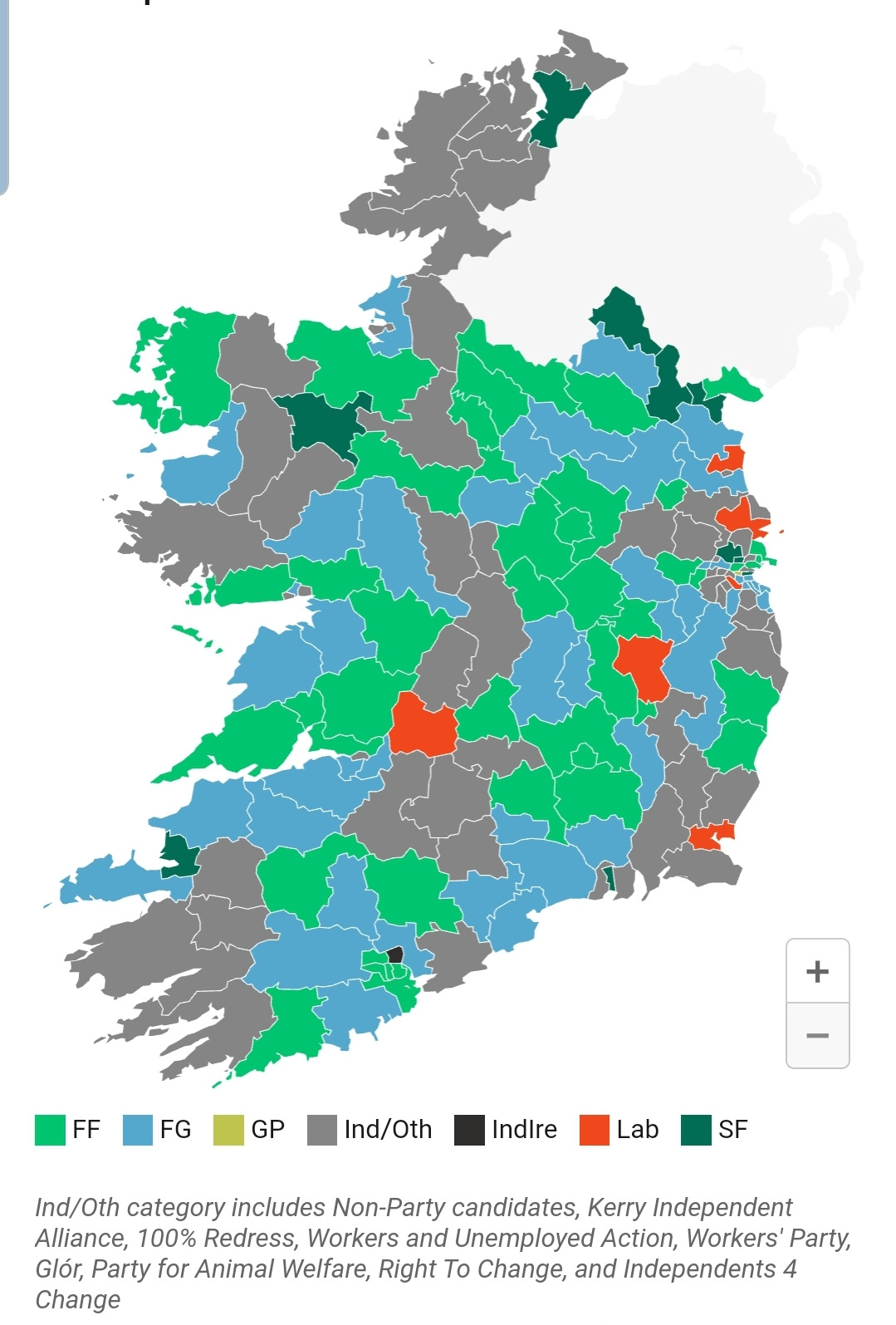

A cursory analysis of electoral maps during the 1980s demonstrate Fianna Fáil’s strongholds tended to be from disadvantaged regions, with rural areas like Donegal South-West and Longford-Westmeath — as well as urban areas like Dublin South-West and of course their leader’s native Northside. This heartland-working class fusion was mirrored in the opposite strategy of Fianna Fáil’s opponents, Fine Gael and Progressive Democrats, which tended to rely on coastal elites, especially in areas like Waterford, Wicklow and of course South-East Dublin (comprising the infamous “D4” district).

The friend and sometime-associate of Haughey, Des Fennell, famously coined this divide as one of ‘Nice People’ and ‘Rednecks’:

‘The Nice People are the Dublin liberal middle class and their allies and supporters throughout the country. The Rednecks are everyone else, but especially Fianna Fáil under Charles Haughey, the great majority of Catholics and their bishops, all Catholic organisations, the IRA and GAA, Sinn Féin, and the Fine Gael dissidents who frustrate Garrett FitzGerald's good intentions.’3

While Haughey and Fianna Fáil were often rash opportunists during this era, Fennell provides the intellectual account of whom they were speaking for (regardless of their motivations or eventual policy) — an of course, whom they were fighting against.

A working-class nationalist alliance

‘Working-class people set much store by loyalty and are generally loyal to persons, parties and the nation. Middle-class people place self-interest, principle and social approval several degrees above loyalty, and their allegiances are therefore more volatile.’4

From his earliest days as party leader, Haughey’s working class roots came in to sharp focus as against the austere backgrounds of former taoisigh such as Castleknock-born Cosgrave and Ballybrack-native Lemass. His long-time rival and leader of Fine Gael, Ballsbridge’s own Garret FitzGerald, was particularly emblematic of this entrenched South Dublin-led establishment. Upon Haughey’s ascent toward the office of Taoiseach, FitzGerald decried the nomination of a man of such ‘a flawed pedigree’.5

Perhaps a motivating factor for this concern was that Haughey’s ‘flawed pedigree’ — coming from Donnycarney — may give him a headstart in relating to the average voter. After their first head-to-head election, this issue certainly arose, as both parties required a coalition with working class Independent TDs in order to form a majority. Fianna Fáil were able to successfully negotiate a conservative-socialist coalition, while FitzGerald was utterly hopeless (as TD Tony Gregory recalled years later):

‘FitzGerald brought an interpreter with him in the form of Jim Mitchel, just in case he couldn't find his way around or understand what we were saying. Haughey was, I think, more of a man of the people to be honest with you. He was a Northsider, we were all Northsiders he had grown up in the general area. He just had that common touch!’6

The Gregory-Fianna Fáil coalition managed to siphon a million-euro stimulus bill to the deprived North Inner-City, an impressive feat during an era defined by brutal austerity measures (regardless of which party was in power). Certainly, the populist economic policy of giving back to working class communities defined much of Haughey’s approach to social policy, as attested for his attachment to wage planning:

‘Haughey justified the wage settlements, in both the public and the private sectors, on the grounds that financial austerity could only create further unemployment in an already rapidly worsening situation. In the circumstances, this was a travesty of Keynesianism’.7

While historian Joe Lee bemoans these wage settlements as “a travesty of Keynesianism”, they were a major contributing factor in Haughey’s popularity. Regardless of financial imprudence, Fianna Fáil continued to demonstrate to working class supporters that they had their back, while making clear that lavish deficit spending had to be cut.

Fennell, himself a former Maoist and staunch critic of Neoliberal Capitalism throughout his life, would often refer to how schemes like this explained why Haughey was (according to polling and electoral results), the most popular politician of the working-class. It also demonstrated for Fennell the silliness of clinging to a rigid political binary:

‘Furthermore, people who talk of the “working-class” as a force on the “Left”, and of Haughey as a threat on the “Right”, are very evidently talking the sort of nonsense usually talked by people who use those threadbare terms today.’8

As an important lesson for Nationalists and Populists today, the successful campaigns of old were not ones explicitly canvassed for “the Right” — they were campaigns for the Nation. In Ireland more than any other European country, to box oneself off as affirming (largely American) foreign political labels (left or right) is an own goal.

Instead, the economic strategy type of Irish populism here was more like a form of patronage — or “parish politics” / corruption, whatever phrase one prefers — which paved the way for a policy of electoral success:

‘This type of neo-corporatism would have been impossible in a government led by Fine Gael, and it took the PDs some time to accept it. The approach reflects Haughey’s personal commitment to cooperation in the national interest, acknowledging the need to maintain Fianna Fáil’s substantial working class and trade union electoral base. Social partnership became a key element in the transformation of the Irish economy in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It sustained industrial peace, wage restraint and deflation, underpinned by government commitments to weaker sectors of the community and welfare recipients.’9

While this type of economic stimulus is an egregious heresy to modern libertarian-infused conservatives, regardless of country, it was an essential step in building a political foundation for traditional Ireland's victories later in the decade. As Tony Gregory said of Haughey, he had secured the trust of much of the working class:

‘On the day the Government fell, I just said that Haughey had acted with honour and integrity towards me and the arrangements he had made. People got houses and a lot of people got jobs in the North Inner-City and in other places. He came up and thanked me for what I had said and I just said “The only reason I had said it was because it was true, and you know it's true so it's no big deal.”’10

The re-awakening of traditional Ireland

‘Consequently, a Yes majority [pro-Life side] will mean, in effect, a declaration by Ireland that it will not conform, in the matter of abortion, to the consumer capitalist empire which surrounds us, which we are part of, and which is pressing us continually to confirm.’11

With the Haugheyite rednecks acquiring the backing of working class communities in inner-city Dublin and elsewhere, they were able to successfully mount a political resistance to the social revolution of the D4 ‘nice people’ — especially as regards FitzGerald’s ‘constitutional crusade’:

‘The campaign for the 8th Amendment split Ireland. The conservative majority drew its support from Fianna Fáil, from rural Ireland and from working-class communities within urban Ireland. The liberal minority drew its support from urban Ireland, especially Dublin, from the middle classes and from younger age groups. During the 1980s the conservative majority successfully imposed its position on the country.’12

By “imposing its position on the country”, Girvan (writing in the Cambridge History of Ireland) means to refer to forging a popular, majoritarian bloc of support, which triumphed democratically both in the 1983 8th Amendment Pro-Life referendum as well as the 1986 15th Amendment Divorce referendum.

Clearly, this populist energy laid the basis for the Catholic resurgence in Irish political life during this period, which Liberals agonise over as being a neo-McQuaid conservative super-culture:

‘There was an air of religious revivalism in response to the Pope’s visit and this was taken advantage of by the Pro-Life Amendment Campaign (PLAC) into securing the insertion of a right to life, anti-abortion, amendment into the constitution. This proved to be the most successful populist campaign ever organised in Ireland.’13

In some ways Haughey and his acolytes were a sharp break from the clear liberalising trajectory of Fianna Fáil (as well as the country writ large) going into the 80s. While there were some radical social policies (particularly in regards to social welfare) supported, generally speaking Ireland bucked the trend of right-wing parties abandoning social conservatism in favour of a liberal defence of market globalisation:

‘Haughey had carefully cultivated the conservative and traditional sections of the party who were suspicious of the modernising group associated with Lynch and the new liberalism evident in other parties. Haughey, while dynamic in some respects, was conservative on constitutional and moral issues and under his leadership the party moved further to the right.’14

While Haughey, with his TV bravado and penchant for straight-talking, did mirror Thatcher and Reagan in superficial ways — his form of populism had little in the way of policy similarity. Thatcher and Reagan were radical supporters of abortion15, as well as mass migration16 — while Haughey’s rednecks forged a forceful illiberal resistance to the global technocratic order.

In his popular Sunday Press column Fennell defended the Pro-Life and anti-divorce campaigns as being an expression of cultural sovereignty as against this Liberalising trend of the global technocratic project. Ireland had planted itself firmly in opposition to the Bolshevism of the Left, as well as the Open Society of Right-wing Capital, epitomised by origin of Thatcher and Reagan’s politics — the Right-Liberal Mont Pelerin Society.

As Britain denied the political sovereignty of Ireland over the North — their proxies also denied our right to cultural autonomy, by forcing in the liberal projects of abortion and divorce into Catholic Ireland. Just as Haughey expressed an independent nationalist foreign policy, opposing the ‘failed political entity’ of Northern Ireland as well supporting Argentina in the Falklands War, he supported the Irish traditional majority’s independence on social issues.

For Fennell, this was revolutionary, as it contradicted the Open Society's insistence on rule by the Few, lest we fall into the paradox of tolerance:

‘[In] all the democracies around us…the constitution and laws are determined by a minority. In Britain for instance, no law is passed which the Catholic Church objects to; in the USA, the Jews and the Union of Longshoremen decide.’17

While I don't know fully of the examples Fennell gives, the point stands, that the post-60s era of ‘democratic Liberalism’ increasingly means a minoritarian rule of specific economic and cultural elites.

The positive takeaway however, is that a resistance movement to cultural and economic Liberalism need not dwell in shadowy reactionary enclaves, it need only offer itself as the democratic will of the people — both in putting bread on the table, and securing a safe and morally secure country.

The dangers of undirected populism

‘We’ve got what we needed, a strong man, able to handle the political and economic challenges now facing the country’, exulted Sile de Valera following Haughey’s election.’18

Perhaps the clearest distinction between this style of Haugheyite Populism, and the neoliberal “conservatism” which preceded (and especially proceeded) the 80s was the base of corporate technocrats who founded Progressive Democrats lead by Des O’Malley. The PDs were in fact a better analogue for the Thatcherite / Reaganite economic neoliberalism which continues to dominate the “intellectual” “right-wing” even today (see fawning support for liberal Javier Milei).

While the PDs may have had the last laugh (in defining much of today's Fianna Fáil policy (of progressive neoliberalism), they were forced to either commit to grovelling coalition governments or dwelling in the opposition during this period. While they were able to pick up support in Dún Laoghaire and some wealthy areas in South Cork, Haughey clearly had most of the inter-urban and rural working class on his side.

The contrast between this corporate liberal right-wing and Haughey’s band of populists was expressed quite literally when Charles McCreevy (part of Fianna Fáil’s moderate wing) put forward a bill of opposition to the government. McCreevy epitomised the neoliberal, anti-family side of the right-wing — he passed the famous tax individualisation bill years later — and so naturally, he clashed violently with working class populists upon leaving Fianna Fáil’s holding of the vote:

‘Crowds of Haughey supporters, many of whom had clearly been drinking, surged forward as McCreevy made his way to his car, jostling him and verbally abusing him. The crowd became even rowdier with Jim Gibbons, who was physically attacked and knocked to the ground. Reports of the event served only to further discredit the Government party.’19

While this incident was unwise and an optical defeat for the party, it reconfirmed that Haughey had awoken a nascent vitalist style of politics within the Irish psyche — for better or worse. The image of a long-dormant Irish working class illiberalism — built around a cult of personality — sent shockwaves across Ballsbridge coffee shops. This was only exacerbated by PJ Mara’s infamous joke, comparing Haughey’s style to certain mid-20th Century authoritarian movements.

It's difficult to emphasise how severe the concern about Haughey’s followers was, but one of the most extreme, yet illustrative, accounts would be that of former Lord Mayor of Dublin, Ben Briscoe, years later recalling the atmosphere of the era:

‘[speaking of the Haughey-era:]"This is it - the dictatorship is here!" 'The days leading up to the vote saw sinister developments. Ben Briscoe who tabled the no-confidence motion, found his roots become a focus of intimidation: "People were ringing up!"' On the day of the motion, a Garda car had to escort him around, and in Briscoe's view, this 'indicates the kind of people who supported him.’20

While this was of course one of the more regrettable incidents of the 80s populist moment, it demonstrates the lengths to which the Haugheyites were willing to go when they felt they weren't being listened to. A style of activism he had acquired in his earliest days as a student in UCD, as FitzGerald would go on to recount his experience witnessing Haughey leading the Anti-British riots during V.E. Day:

‘I was in town celebrating and I discovered that there was some kind of riot or something taking place in college green, because Charlie Haughey had taken down British flags flying over Trinity. There was a battle charge, and we escaped by jumping over bicycles and going up Trinity Street. But obviously my views and his would have been different. I was strongly pro-allied, as my friends would have been, but I don't think he shared that view at all.’21

And really, one can clearly identify the illiberal and majoritarian strands to the movement by listening to it's officially endorsed anthem. Roaring out at mega-rallies that the people must ‘Hail the Leader’ borders on the comedic for today's political vocabulary. The use of anthems like A Nation Once Again upon being elected also reinforce this illiberal, vitalist form of political rhetoric.

Fennell himself seemed to recognise this, in his article ‘Germans fear their own folk songs’, in which he highlights the popularity of the muscular Irish-redneck rebel songs with Germans — even and especially the most anti-national of them. Fennell writes of a popular rebel singer in Hamburg, such as one would in a Haughey rally, roaring out A Nation Once Again to great cheer, only to cause severe shock and consternation when he ended the song ‘And Germany too!’. For these Germans, they loved Irish rebel music for the same reason they were terrified of their own culture — it alluded to a dangerous, pre-liberal and triumphant form of cultural independence, unbeholden to the provinciality of the post-war Anglo-American consumer-empire:

'Germany was "occupied" every bit as much as Northern Ireland—occupied by Americans, Russians and, indeed by some Brits—he met a shaking of heads and total acceptance of the "colonial" status quo as preferable to the alternative of a re-united Germany.'22

In some sense, Ireland during the 1980s experienced a brief glimpse of what a burgeoning majoritarian sovereignty movement looks like — if one that desperately needed the intellectual and policy driven guidance of oft-under utilised (on the Right at least) figures like Fennell.

Is there a future for Neo-Haugheyites?

Despite these revolutionary aspects of the 80s era, the Haugheyite mass-movement largely died as his career ended. While there were subtle indications that its energy still existed — the 2004 Citizenship referendum being one — there was no such identifiable mass-populism during the Celtic Tiger period.

The question for populists going forward is how exactly mass-popular feelings about sovereignty and national independence can be steered toward a productive and focused science of political policy — as opposed to undirected mob activism.

The Haughey-era did see tremendous electoral victories, but it was ultimately unable to craft a legitimately alternative apparatus of political policy. The importance of Fennell in this regard is in providing an intellectual formulation of a populist ideology, which stands the test of time. One thinks Fennell’s framing of the political struggle of being between the Neoliberal, Capitalist D4-technocracy (‘the Nice People’), as against the working class and socially traditional majority (‘the Rednecks’) may be seen to be essential.

‘[what] I called in a lecture given in the US last October the “Political Science approach” — was developed in my Sunday Press column. … I look forward to the day when this will no longer be regarded as eccentric Fennellism for the simple reason that it has become as commonplace throughout Ireland as the repetitive orthodox thinking now is.’23

Bibliography

Fennell, Desmond. 1984. Irish Catholics and Freedom since 1916. Dominican, Dublin.

—1984. Cuireadh chun na Tríú Réabhlóide

—1986. Nice People & Rednecks: Ireland in the 1980s. Gill and Macmillan Ltd, Dublin.

—1987. A Connacht Journey. Gill and Macmillan Ltd, Dublin.

—1989. The Revision of Irish Nationalism.

—1993. Heresy: The Battle of Ideas in Modern Ireland.

Girvan, Brian. 2018. ‘Ireland Transformed? Modernisation, Secularisation and Conservatism since 1973’ in Part III - Contemporary Ireland, 1945–2016. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, J.J., 1989. Ireland 1912–1985 - Politics and Society, Cambridge University Press.

Whelan, Noel. 2011. Fianna Fail: A Biography of the Party. Macmillan ltd.

*This essay is the first in a series on the political philosophy of Desmond Fennell, and how the man’s thought relates to modern Ireland.

Fennell, Nice People & Rednecks, p. vii.

Ibid.

Ibid, p. 93.

Whelan, p. 253.

Haughey - Episode Three, 6:26-49.

Lee, p. 502.

Fennell, Nice People & Rednecks, p. 90.

Girvan, p. 4.

Haughey - Episode Three, 30:43-31:04.

Fennell, Nice People & Rednecks, p. 76.

Girvan, p. 423.

Girvan, p. 421.

Girvan, p. 415-6.

Reagan implemented the Therapeutic Abortion Act in May 1967, the most Liberal abortion law in the country at that time. Thatcher spoke in favour of abortion (Vol. 732. House of Commons. 22 July 1966) and supported legalisation of Homosexuality.

Thatcher supported the European Economic Community, as well as Somali immigration into Britain. Reagan single-handedly turned California into a Democratic state through supporting amnesty.

Fennell, Nice People & Rednecks, p. 83.

Lee, p.500.

Whelan, p. 268.

Haughey - Episode One, 39:34-40:07.

Ibid, 14:21-14:49.

‘Germans fear their own folk songs’, Sunday Press, 22-07-1984.

Fennell, Nice People & Rednecks, xvii.