"The land of Ireland for the people of Ireland": the perennial spectre of the Land War in Irish Nationalism

Irish Nationalists have always believed in the right of the majority to rule in their communities.

Community Autonomy and Irish Nationalism

Since the 1170 invasion of Strongbow and Josce the Irish nation has not been afforded its right to self-determination and control over its own land. Irish Nationalists have always had to remind the world — and ourselves — of that right. This is a brief compilation of their arguments.

Young Ireland, Lalor and Mitchel’s notion of the right to Land in the 1840s

Starting in the late 1700s with the Whiteboys' tenant revolts, and culminating in 1798 with Wolfe Tone’s advocacy for the ‘men of no property’, the issue of Land rights was central to the formation of Irish Nationalism.

With the start of the famine in 1845, Nationalists in the Young Ireland movement began to emphasise the rights of communities over their own land to a more explicit degree. The two most prominent figures in this regard were James Fintan Lalor and John Mitchel, who formulated the difference between mere ‘property’ and ancestral ‘soil’:

‘Two writers in particular, James Fintan Lalor and Michael Davitt, made the distinction between these terms a central feature of their political programmes. In effect, ownership of the soil was interpreted by them as a national right; ownership of the land was an individual claim.’1

For these two figures the cause of Ireland was wrapped up in the cause of community self-determination. No legal contract, foreign conquest or economic claim superseded the right of the people, or the Nation, to their own soil. It is a metaphysical bond awarded by God. This is why the motto of the Young Ireland newspaper, The Nation, was ‘To foster a public opinion and make it racy of the soil.’2 — meaning a unified cultural people, who are tied to and affirm their land. Lalor put it better than any other polemicist could:

‘Ireland her own – Ireland her own, and all therein, from the sod to the sky. The soil of Ireland for the people of Ireland, to have and to hold from God alone who gave it – to have and to hold to them and their heirs for ever, without suit or service, faith or fealty, rent or render, to any power under Heaven.’3

At the time of writing this, the British landlord system was brutally tyrannizing the native tenants. While the Potato blight worsened through to Black 47', the Liberal British government showed no remorse, utilizing ‘scientific’ Malthusian arguments so that, in one historian’s description, the ‘population would decay or vanish and become extinct at once’.4 As peasants and tenants revolted across the country, from Tipperary to Kilkenny, claiming Irish land back for the Irish people, John Mitchel saw a spiritual battle for our ancient birthright. In the article For Land and Life!, he wrote:

‘“Ireland for the Irish” means primarily and mainly, not “Irishmen for Irish offices,” not “political ameliorations,” not “assimilation to English franchises” – patient Heaven! no; – it means, first, Irishmen fixed upon Irish ground, and growing there, occupying the island like trees in a living forest with roots stretching as far towards Tartarus as their heads lift themselves towards the clouds. In such a nation as this, industry, energy, virtue become possible’.

Parnell & Davitt and their Land War of the 1880s

After the failure of Young Ireland it took the Land League in the 1880s to see a revival of the Land War concept. With the Long Depression of the 1870s and the Famine of 79’ causing a further destabilisation of the land tenure system of the British, Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt, among others, started to gather around the issue of winning back Irish land. The Land League began with ‘monster meetings’ in Mayo, proclaiming ‘The Land of Ireland for the people of Ireland’ — Lalor’s phrase. Parnell argued that it was time once again for the Irish nation to peacefully advocate for land renationalisation:

‘You can never have civil liberty so long as strangers and Englishmen make your laws and so long as the occupiers of the soil own not an inch of it.’5

In his “No Rent” Manifesto (1881) Parnell advocated for civil disobedience, starting protests and refusing to pay taxes to the British and foreign rule. He urged the Irish nation to ‘Stand together in face of the brutal, cowardly enemies of your race!’ — meaning both the British imperialists as well as the centrists who stand in the people’s way of achieving self-determination.6 Michael Davitt endorsed much of this project, incorporating the economic view of Georgism, which asserts that all land of the country should be taxed universally by the State, in order to cut property spongers and speculators. The crux of the movement was that of men against modern Liberalism.

As Foster describes:

‘How far did the Land League raise nationalist consciousness? According to a modern authority 'the League fostered, where it did not articulate, the identification of basic local demands with wider political issues, which in themselves lacked much meaning for the peasantry'. It certainly reinforced the politicization of rural Catholic nationalist Ireland, partly by defining that identity against urbanization, landlordism, Englishness and — implicitly — Protestantism.’7

The Revolutionary Period

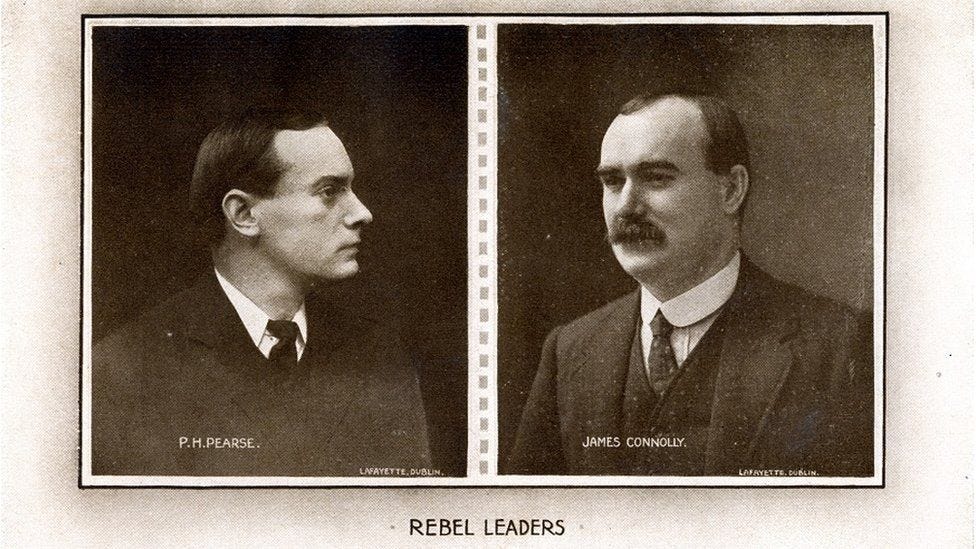

The issue of land ownership arose again in the revolutionary climate leading to the 1916 Easter Rising. James Connolly, as a socialist, believed strongly in Irish land for Irish people:

‘Property of all kinds ought to be subject to the community, and if the welfare of the community requires that ‘legal’ rights of property shall be subordinated, or even totally set aside, it must be done.’8

While never quite as statist, Pádraig Pearse similarly considered the idea of national ownership of land:

‘A nation may, for instance, determine, as the free Irish nation determined and enforced for many centuries, that private ownership shall not exist in land; that the whole of a nation’s soil is the public property of the nation.’9

Under De Valera and the eventual Free State, compromises were made between large landowners and small tennants. The issue of a national land revolt would not arise again for some time.

The Anti-Globalisation Revolt of the 1960s

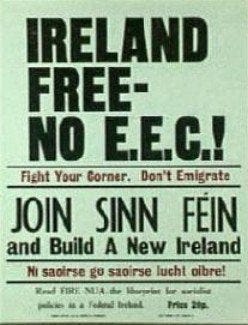

With the beginning of EEC negotiations and the globalisation of land under successive governments, there was a short period of land revolt in the 1960s. American Corporations and wealthy migration from Germany began to cause discontent among disparate communities. Many local people felt the influx of new Capital and people was driving up housing prices and creating new competition with native producers. This lead to the perennial calls for Land advocacy:

‘A curious feature of the hostility shown towards foreigners buying land was the reappearance of an organisation bearing the subtitle 'land league', insisting the government should buy back land owned by foreigners to raise uneconomic holdings to a more profitable level. Gradually, such sentiments took on a more racist tone, with county committees of agriculture demanding that the government 'preclude aliens from acquiring land in Ireland.'

The National Land League exploited fears by asserting that 'the land of Ireland for the people of Ireland has as much meaning today as it had in Lalor's day, and no other solution will be tolerated by this or any future generation of Irishmen or women'.’10

Feelings of discontent across the country were widespread. The transition from Traditional Ireland to Global Ireland was not a pretty one. In Banagher, Offaly, riots broke out between a radical priest and his followers over a dispute of government taking communal land.11 Smaller parties like Clann Na Saoirse began to rise up too, speaking out against the rise in urbanised globalisation, arguing that economic Liberalism was selling out the country to foreigners.12 Provisional Sinn Féin concurred, arguing in their document Nation or Province?: Ireland and the Common Market, in a section called ‘The Influx of Foreigners’:

‘The labour force within Ireland, of which there are currently over 98,000 unemployed, will be further increased by the influx of foreigners in search of employment and prepared to sell their services at a cheaper rate of pay than what is currently the rate of pay to native workers.’13

Even the great late poet Thomas Kinsella noted the selling out of the Irish nation, in perhaps his most famous poem, Nightwalker:

‘The poet Thomas Kinsella, who worked in the Department of Finance, also dealt with the German investors issue in his poem 'Nightwalker', satirising the department officials who boasted about:

'our labour pool

the tax concessions to foreign capital

how to get a nice estate through German.'’14

Generally, this did not amount to much. We entered the EEC, continued the trend of economic globalisation and we are where we are today. But what is important is the furthering of the tradition of land revolts by the Irish people.

Provincialised Ireland in the 2020s: the rise of A Nation Once Again?

With Ireland being more globalised than it has ever been, the question arises for what is to become of the country today. There could be a rise in a new Land War. Is it possible that the 2020s sees a re-emergence of Irish Land advocacy? Only time shall tell.

Bibliography

Deane, Seamus. 1994. Land & Soil: a territorial rhetoric by Seamus Deane. History Ireland.

Ferriter, Diarmaid. 2004. The Transformation of Ireland, 1900-2000. London: Profile.

Foster, R. F. 1988. Modern Ireland 1600-1972. London: Allen Lane.

Lee, Joseph. 1989. Ireland, 1912-1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge;New York;: Cambridge University Press.

McGrail, Courtney. 2015. Racy of the soil. The Irish Catholic.

Deane.

Catholic Observer.

Deane.

Deane.

Speech in Navan (12 October 1879), quoted in F. S. L. Lyons, Charles Stewart Parnell [1977] (1991), p. 96.

"No Rent Manifesto" (18 October 1881).

Foster, p.415.

Connolly, James. 1889. The Irish Land Question.

Pearse, P.H.. 1916. The Sovereign People.

Ferriter, p.247.

Madden, Jim. 2012. Fr John Fahy, Radical Republican & Agrarian Activist (1893-1969). Dublin.

Clann Na Saoirse, "The Others" The Alan Kinsella Podcast.

Nation or Province, p.3.

Ferriter, p.548.