'Up to Monto': A centenary of the Legion's victory for family and social justice

This March marked the one hundred year anniversary of one of the few historic achievements of the Irish Free State, which prioritised family and subsidiarity for generations.

The Monto's Hellish slums and British-occupied Dublin city

And take her up to Monto, Monto, Monto, Take her up to Monto, lan-ge- roo, To you!—Monto.

spoke a word of caution re the dangers of nighttown, women of ill fame and swell mobsmen, which, barely permissible once in a while though not as a habitual practice, was of the nature of a regular deathtrap for young fellows of his age—Ulysses, p. 993.

With the recent scandal over rampant abuse and neglect in Irish care homes, the sanctimonious narrative of ‘Dev’s prison island’ compared to our modern ‘liberated utopia’ is once again coming undone. Speaking accurately, modern Dublin’s neglect, poverty and commercialisation of abuse seen is more akin to pre-Dev British Dublin, the exact behemoth that the Independence generation were fighting against. In all of the history of the city, there are few areas which define this tension between nationalist humanism and globalist abandonment than in the famous prostitution racket of Montgomery street—as well as the successful movement to dislodge it.

The Monto, a notorious red-light district in Dublin, operated from around the 1860s until its closure in 1925. Located just off what is now O'Connell Street, its name was derived from, as stated above, Montgomery Street (now Foley Street). This small area, sometimes referred to as a ‘square mile’ or ‘mere dot on the landscape,’ gained a reputation that stretched across Europe and America.

The conditions within Monto were often described as squalid and dangerous, reflecting the pervasive poverty and crime of the area, once put as a ‘thriving den of iniquity hidden in plain sight’. It was characterized by:

debauchery, vice and crime. Tenement houses, pawnshops, pubs, shebeens, cellars and secret passages, brothels, decaying buildings, dampness, filth and smells – all were part of the magic, mystery and horror of this mayhem.—Curtis, “To Hell or to Monto”.1

Abuse was common, and women ‘suffered from syphilis and sexual violence’. One local resident recalled ‘the sight of working girls having to sometimes sleep in the doorways of houses when the madams would not let them in for the night. They went through hell’ (ibid). A medical student observed in 1904 that ‘in no other capital of Europe have I seen its equal’ in terms of the squalor and abandonment of the girls in the area.

Contrary to today’s promoted notion that “sex-work” is empowering for the girls involved, the monto frequently enforced ‘brutal’ and ‘horrific punishments’ for those that did not step in line:

Physical abuse was frequent, with “Black eyes, broken arms and dumped girls sleeping in doorways” being a “regular sight in Monto”.

The district was run like the ruthless capitalist enterprise that it was. There was a sophisticated superstructure imposing order and retribution on all imvolved. Often requiring cruel and degrading treatment including beatings by the madams, the ‘bully boys’ or ‘fancy men’, as wel the drunken and callous customers.

As the enforcers of this system, the Madams maintained control through debt bondage:

The madams would keep the girls in debt, rent them the latest fashions and ditch them out onto the street when they became pregnant or...“when the effects of their lifestyle began to show…”. Girls were forced to buy expensive wardrobes at inflated prices and could not leave until their “indebtedness had been wiped out”. As one girl stated, “We've simply got to stick and that's all there is to it”.

One madam, May Oblong, was known to have ‘slashed girls' faces and had some gang-raped by up to thirty men if they crossed her’.

The “prime age” of prostitutes for some customers in the Monto was as young as 12, and it was only a partial shock when ‘a child of these exact years was kidnapped and found in Monto’. At the time, the age of consent was 13, and girls were ‘kicked out of the workhouse at 13, expected to be independent adults’.

To add to the wretched nature of the place, venereal disease ran rampant throughout the congested and overpopulated streets. In a sense this was an homage to the 1840s, when the An Gorta Mór forced a fresh new generation of young girls into a type of slavery, where desperate families would sell their children to sex work in the hopes of getting the funds to survive.

Sexual slavery in early 20th Century Capitalism

Much like the parasitical gombeenism of the Famine era, the Monto was also heavily enmeshed in a broader transnational powerstructure. Partially as a relief valve of sorts for the British army, London's administrative elites made great use of the district as a financial and colonial operation.

Wealthier clientele from across the British empire also enjoyed the fruits of its ‘labour’. For generations, rumours abounded of supposed evidence of secret access and exclusive establishments in the Monto for British colonial elites. Much like Epstein rings or other such topics which cranks and journalists alike obsess over today:

King Edward VII, while still the Prince of Wales, was “reputed to have lost his virginity there” and “would have accessed Monto through some of the secret tunnels that were dotted all over Monto”.

Usually, this type of talk—of secret tunnels leading to the debauched activities of the British royalty—deserves a swift dismissal and rejection. But in this case, it does appear to have some grounding in reality:

These tunnels were discovered during demolitions, with “One of the passageways discovered ran in the direction of the Custom House,” suggesting use by VIPs.

Most likely, these tunnel networks guided their beneficiaries further up Mecklenburgh Street, where ‘flash houses’ offered a more respectable production. This was ‘patronised by politicians and the gentry after dark’ where they ‘arrived in curtained cabs or motor cars’. One can only imagine the vast array of rumours and conspiracies swirling around Dublin at the time about the mysterious activities of elites within the Monto’s maze of squalid laneways and alleyways.

In many ways, there were no better symbols of the matrix of British control and exploitation over Dublin—as well as the opaque nature of it. Tucked away from the Catholic gaelic majority of the country, foreign elites practiced debauchery in a ‘labyrinth of rooms, mirrors, false doors, secret passages, and a dungeon for the unwanted customers’.

While Monto was a distinctly Dublin enterprise, it also drew from and interacted with a broader international context, especially through its clientele and the origins of some madams: ‘Some of the madams of Monto...Some were Dublin women; others come from elsewhere in Ireland; others still come from England and Scotland.’

The area’s proximity to Dublin's port meant that ‘droves of sailors and seaman flocked to Monto when their ships docked. These ships would have been laden with nationalities from every corner of the world’, suggesting a diverse international clientele.

Monto shared characteristics with other global sex trade centers and was recognized as a significant hub in its era. It was ‘reputed to be the biggest red-light district in Europe at the time’. Its notoriety was such that it was mentioned in the Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1903, explicitly comparing its openness to practices ‘in the south of Europe or in Algeria’. In her biography of Frank Duff, Finola Kennedy details how the British used this trade as part of the capitalist migration racket of their empire:

Mary Purcell provides historical background to the settlement near Aldborough Barracks, in the Monto area, of the returning 'Castrensi, or camp followers of the victorious army in the Crimean war. She says that “The authorities took one look at these foreigners from every country in Europe and promptly shipped them to Dublin.”—Kennedy, Finola.

While in part moral panic, there was an extreme reality at the time of European-based prostitution rings, making the Monto itself part of a global phenomenon. It is extensively discussed as an ‘international traffic in white women’ that existed across ‘Europe, North America, Panama, South America, Egypt and other parts of Africa, India, China and Japan’. Naturally, this enraged many different groups, ranging from feminists and progressives to ultra-religious social conservatives.

This global trade itself was supported and characterised by ‘organized, ramified and well-equipped associations’ that operated with ‘large capital, representatives in various countries, well paid agents, and able, high salaried lawyers’. In that case, a rising grass-roots movement in the United States and Britain grew through the social purity movement, in which many feminists successfully fought for rights we take for granted today—such as modern age of consent laws.

For the Monto, what was required was a Irish-based grassroots and religiously inspired crusade to upend this wretched matrix of capitalist exploitation and female abuse.

Legionaries and the rise of Catholic social justice

Thankfully, tireless work from organised social groups and civic society organisations began to demonstrate resistance to the Monto’s exploitation and evils. This movement was largely driven by Irish Catholic and nationalist forces who sought to moralize the new Free State:

the determination of the Catholic Action group the Legion of Mary and its leader, Frank Duff, to close Monto, and the encouragement of Fr Richard Devane of the Jesuits, all combined to end the reign of the most notorious red-light district in Europe.

The Legion first led the way in seeking to reform and ultimately end the brutal conditions of the district. They started with efforts of visiting brothels and persuading women to attend retreats and relief centres, organised and paid for by the Legionaries themselves. Their greatest early success was in the acquisition of 75 Harcourt Street, which was transferred into the Sancta Maria hostel, providing bedding and new clothes to young girls who agreed to leave the Monto’s clutches.

The building itself had a sort of providential air to it, as it was formerly used by Sinn Féin and Michael Collins as a secret safe-house and escape route during the War of Independence. Then under the ownership of Sinn Féiner Batt O’Connor, it was now in part occupied by his daughter, Eileen O’Connor, on behalf of the Legion. While the two movements had nominally distinct aims, political freedom as against social-spiritual welfare, in many ways they were inseparable. Reading of the Legion's remoulding of the building, one is struck by the spiritual significance of the process, quite akin to the wider movement of re-Gaelicisation of the streetnames and sacred places around the country at that time:

‘pictiúr den Chroí Ró-Naofa agus chuir ar crochadh é san iostas nua, agus rinne siad searmannas 'Ríú an Chroí Naofa' an pictiúr a chrochadh in áit chuí agus an teach agus an comhluadar a chur faoi Choimirce an Chroí Ró-Naofa. Is fíor a rá go ndearnadh éacht oibre an lá sin’—de Vál, lth. 46.

As the stories of the girls from the Monto began to come out, and spread across Catholic papers and parishes, a strong momentum developed in favor of closing the district for good. They described the damp and brutal conditions, one image of eight young girls sitting together in a ring passing around methylated spirits and water becoming quite famous. The scandal reached its apex at the image of the funeral of little Mary Tate, a particularly young girl who was abandoned to fatal disease by her madam, May Oblong. With the desperate attempts by volunteers to bring her to hospital, her death demonstrated the necessity of state action to clean up the street.

As best as the powerful bullies, pimps and brothel-keepers attempted to soften the image of the abuse, the reality had gotten out. The public began to widely view their practices as exploiting those little girls like Mary Tate, the symbol of ‘the battered type that had been on the streets for a great number of years and who had sunk with every day, perpetual drinkers, clad in rags, whose appearance was generally dreadful’. The Jesuits, scandalized by Monto, ‘precipitated the gathering and galvanising of Catholic forces in the new Irish Free State, to go on the attack once and for all that rid the city of Monto’.

This campaign culminated in a ‘large-scale police raid on Monto for 12 March 1925’ with the cooperation of Dublin Police Commissioner, General William Murphy, resulting in 120 arrests and the closure of the brothels. Following the raid:

members of the Legion marching into Monto, past the remaining kneeling prostitutes, blessing each brothel and pinning a religious picture to each door. Frank Duff went to the back of Corporation Buildings...and proceeded to hang a huge crucifix to the wall, sending a clear message that the days of Monto were well and truly over.

Previously, Duff had noted how Monto was ‘Known to all, and free from police interference’. Where the British had neglected and exploited the young girls of the area, Catholics and Nationalists reclaimed the street in act of heroism on the part of realising a purified Irish-Ireland.

Taken in this light, the righteous crusade of the Legion against the Monto should be celebrated as a triumphant step toward a spiritually liberated Ireland. What else but the British slums of prostitution, disease and poverty could be used as the essential image of occupation of our great island?

Reasserting the closure of the Monto as an act of Catholic-nationalist solidarity

Certainly, patriots have long interpreted the event this way. Irish nationalists at the time believed that ‘prostitution and venereal disease were symptoms of the British presence in Ireland and that it was only with Irish independence that they would disappear’. The district's existence was closely tied to the presence of British military forces and their official tolerance of prostitution: ‘Nationalists repeatedly linked the very existence of the district to the presence of the British military in Ireland’.

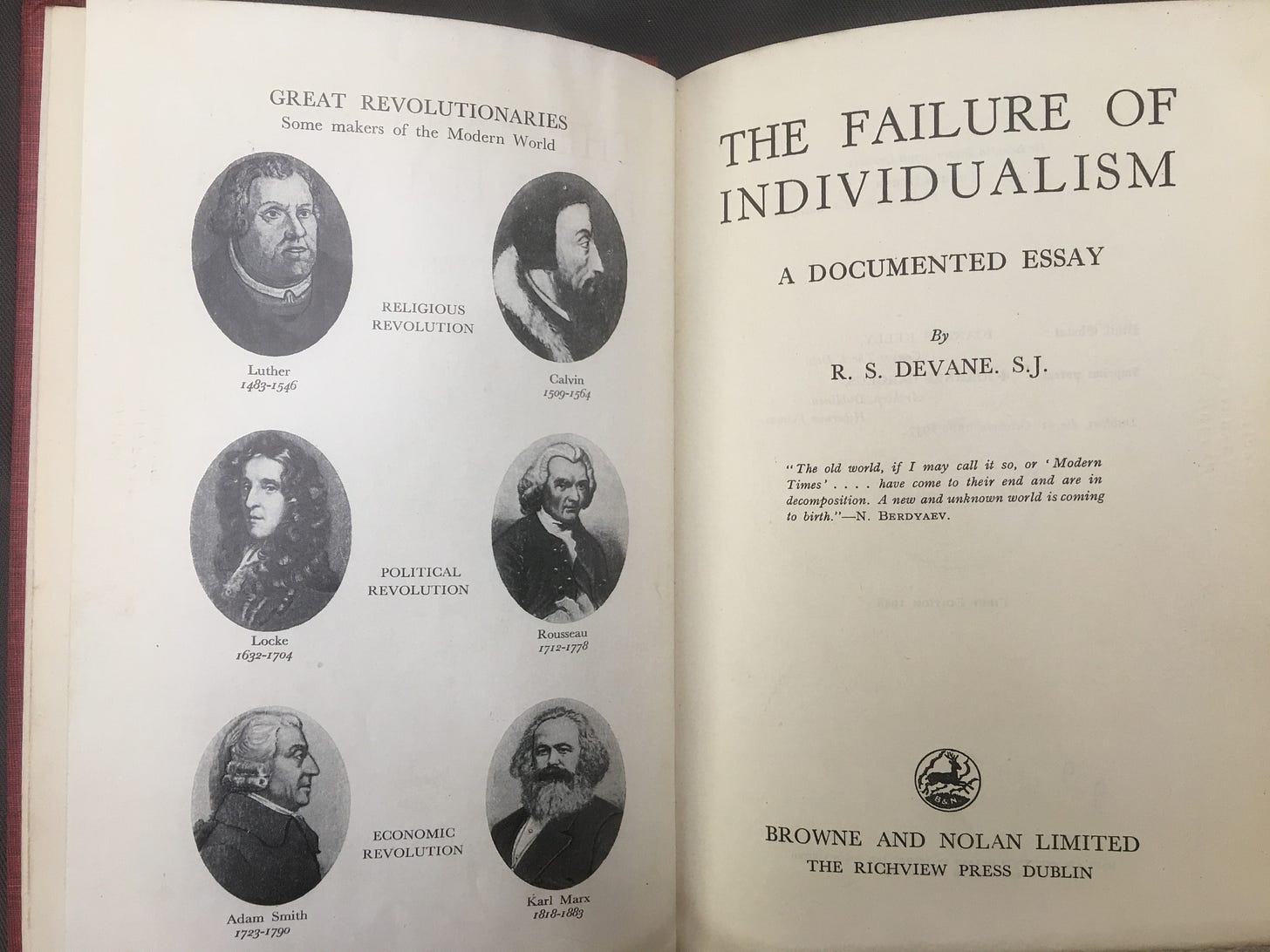

Irish-Irelanders, often members of the Legion itself, saw their goal of the re-nationalisation of the country as a primarily cultural and spiritual battle. The anglicisation of our social life retarded and degraded its moral quality, as the great Legionary, and organiser against the Monto, Richard Devane S.J. viewed it. Laid out in his 1948 book ‘The Failure of Individualism’, Devane:

‘argued that, because of individualism, economic and political systems had failed…Irish people had lived individual lives up to this point; it was time now to focus on the welfare of the community. In his mind, the youth of the late 1940s had an opportunity to abandon selfishness and self-interest. In doing so they would create an Ireland based on the aspirations of their parents.’ Walsh, Martin, 2014. “Richard Devane: Social Campaigner”, Studies, p. 570.

There would be no point if we were to achieve a nominally ‘independent’ country, but one which was still populated by ‘intellectual slaves’ in the ‘stranglehold of an alien press’. Whether it be rampant prostitution rings or globalist consumerism, the biggest threat facing the spiritual reconquest of Ireland was an individualist ethic which negated the state and community welfare organisations like the Legion. Unfortunately, despite the constant claims of the ‘Dev’s Prison island’-brigade, the radical corporatist dream of the Legion and Devane was never implemented:

‘From the 1950s onwards, Ireland began to move away from the economic policies of protectionism and embrace the ideas of an open market economy, bringing new cultural influences in its wake. The fears Fr Devane had expressed in 1948 about the individualism of youth were about to be realised. Instead of espousing the idea he had advocated of creating a uniquely Irish culture, the young people of the following decades would embrace, instead, many of the foreign cultural influences against which he had for so long campaigned.’ Ibid.

With the dispelling of prostitution by way of the Monto, a new dawn was suggested for the Saorstát; a spiritually and culturally replenished Irish-Ireland ideal. The country was to be de-Anglicised and made again in the Faith of the monks and traditional gaeldom.

Unfortunately, this obviously didn’t come to pass. Despite the constant claims of Dev’s Gaelicist-Catholic-Republican ‘prison island’ autocracy—all true believers know the Free State largely abandoned most of its early ideals quite quickly. Fíorghaeil, God-fearing Catholics and those loyal to the first Dáil know this oh too well.

Still, the case of the Monto allows us to dream about what could’ve been, as well as envision what could still be. Its example forcibly reminds one of the barren commercialisation, globalism and cultural slop—not to mention the economic exploitation, aesthetic pollution and outright architectural decay of our major cities today. Dublin, Belfast and elsewhere are grim images of neglect. Compared to the 1920s Free State, these examples provide a harrowing, but nonetheless exhilarating, impetus to imagine tearing them all down and forging the new cities of a spiritually purified and liberated Irish-Ireland.

Bibliography

Curtis, Maurice. 2015. To Hell or to Monto.

De Vál, Séamas S.. 2009. Frank Duff.

Kennedy, Finola. 2007. Frank Duff: A Life Story.

When not stated, assume a quote is from Curtis work.

Used to work in this area of Dublin. So much history. There are Monto Tours run by a lad who collected loads of stories, furniture and artefacts from the tumbledown tenements :

Monto walking tour on, this Saturday, 21st June. Time: 2 PM.

Meet outside the Spar Shop at the very end of Talbot Street, right facing Connolly Train Station on Amiens Street, D 1.

The tour 2 hours. Costs €10 per/person. (No booking is required.)

What a phrase "parasitical gombeenism". Brilliant writing. Clear from any reading of the Famine period that a certain section of the Irish did very well out of things. Middlemen, grabbers, parasites.

Parasitical gombeenism is a perfect description of our rent seeking society, you don't have to charge a young family market rent, you know. Usury and grabbing is where it's at now.